Monthly Archives: March 2014

New Blog Design (Updated with Poll)

Adorno on the Institute for Deaf-Mutes

I ran across this passage by the philosopher Theodor Adorno in Minima Moralia, a collection of aphorisms and observations. That’s Adorno’s desk in a park in Frankfurt above, which I took the last time I was there. The passage is a remarkable comment on speech and human existence, but I will not provide any comments on it myself. (Rather busy at the moment, I’m afraid.) What do you think about the passage?

[90] Institute for deaf-mutes. – While the schools drill human beings in speech as in first aid for the victims of traffic accidents and in the construction of gliders, the schooled ones become ever more silent. They can give speeches, every sentence qualifies them for the microphone, before which they can be placed as representatives of the average, but the capacity to speak with each other is being suffocated. It presupposes an experience worthy of being communicated, freedom of expression, and independence as much as social relations. In the all-encompassing system conversation turns into ventriloquism. Everyone is their own Charlie McCarthy: thus the latter’s popularity. Words are turning altogether into the formulas, which were previously reserved for greetings and farewells. For example, a young lady successfully raised according to the latest desiderata should be able to say, at every moment, what is appropriate in a “situation,” according to tried and true guidelines. However such determinism of speech through adaptation is its end: the relation between the thing and the expression is severed, and just as the concepts of the positivists are supposed to be nothing more than placeholders, those of positivistic humanity are literally turned into coins. What is happening in the voices of the speakers, is what, according to the insight of psychology, happened to that of the conscience, from whose resonance all speech lives: it is replaced down to the most refined cadence by a socially prepared mechanism. As soon as this last stops functioning, creating pauses, unforeseen by unwritten statutes of law, panic ensures. This has led to the rise of intricate games and other free-time activities, which are supposed to dispense with the burden of conscience of speech. The shadow of fear however falls ominously on the speech which remains. Impartiality and objectivity in the discussion of objects are disappearing even in the most intimate circles, just as in politics, where the discussion was long since dispelled by the word of power. Speaking is taking on a malign gesture. It is becoming sportified. One tries to score as many points as possible: there is no conversation which the opportunity for competition does not worm itself into, like a poison. The emotions generated by the subjects being discussed, in conversations worthy of human beings, attach themselves pigheadedly to the narrow issue of who is right, outside of any relationship to the relevance of the statement. As a pure means of power, however, the disenchanted word exerts a magical power over those who use it. It can be observed time and time again how something once uttered, no matter how absurd, accidental or incorrect, precisely because it was once said, tyrannizes the speaker like a possession they cannot break away from. Words, numbers, and meetings, once concocted and expressed, become independent and bring all manner of calamity to those in their vicinity. They form a zone of paranoid infection, and it requires the maximum reason to break their baleful spell. The magicalization of the great and inconsequential political slogans is repeated privately, in the seemingly most neutral of objects: the rigor mortis of society is overtaking even the cells of intimacy, which thought themselves protected from it. Nothing is being done to humanity from the outside only: dumbness is the objective Spirit [Geist].

Is Culture the Solution or the Problem?

Just the other week, I wrote a post (here) on the importance of recognizing the problems with using the concept of culture to understand Deaf social relations. I just came across a great article about immigrant sociology that makes the same point called “Herder’s Heritage” for short. I will quote from it at length because the argument is much better than the one I made. The final paragraph is the most important one, and it corresponds to points #1–4 on my earlier post What do sign language interpreters need to accomplish? In other words, I think the framework that interpreters use to understand “Deaf culture”, and indeed the framework that has been taught to many in the Deaf community, needs massive revision. Andreas Wimmer explains why:

“In the eyes of 18th-century philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, the social world was populated by distinct peoples, analogous to the species of the natural world. Rather than dividing humanity into “races” depending on physical appearance and innate character (Herder 1968:179) or ranking peoples on the basis of their civiliza- tional achievements (Herder 1968:207, 227), as was common in French and British writings of the time, Herder insisted that each people represented one distinctive manifestation of a shared human capacity for cultivation (or Bildung) (e.g. 1968:226; but see Berg 1990 for Herder’s ambiguities regarding the equality of peoples).

Herder’s account of world history, conveyed in his sprawling and encyclopedic Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit, tells of the emergence and dis- appearance of different peoples, their cultural flourishing and decline, their migra- tions and adaptations to local habitat, and their mutual displacement, conquest, and subjugation. Each of these peoples was defined by three characteristics. First, each forms a community held together by close ties among its members (cf. 1968:407), or, in the words of the founder of romantic political theory Adam Mu ̈ller, a “Volksge- meinschaft.” Secondly, each people has a consciousness of itself, an identity based on a sense of shared destiny and historical continuity (1968:325). And finally, each people is endowed with its own culture and language that define a unique worldview, the “Genius eines Volkes” in Herderian language (cf. 1968:234). …

But I should first discuss Herder’s heritage, which has left its mark not only on his direct descendants in folklore studies and cultural anthropology (Berg 1990; Wimmer 1996), but also on sociology and history.

In the following review, I will limit the discussion—for better or for worse—to North American intellectual currents, which are a source of inspiration to many discussions in other national contexts, and to three sets of approaches: various strands of assimilation theory, multiculturalism, and ethnic studies. As we will see, these paradigms rely on Herderian ontology to different degrees and emphasize different elements of the Herderian trinity of ethnic community, culture, and identity. They all concur, however, in taking ethnic groups as self-evident units of analysis and observation, assuming that dividing an immigrant society along ethnic lines—rather than class, religion, and so forth—is the most adequate way of advancing empirical understanding of immigrant incorporation. …

In conclusion, we can gain considerable analytical leverage if we conceive of immigrant incorporation [or Deaf social relations] as the outcome of a struggle over the boundaries of inclusion in which all members of a society are involved, including institutional actors such as civil society organizations, various state agencies, and so on. By focusing on these struggles, the ethnic group formation paradigm helps to avoid the Herderian ontology, in which ethnic communities appear as the given building blocks of society, rather than as the outcome of specific social processes in need of comparative explanation.”

Wimmer, A. (2009). Herder’s Heritage and the Boundary‐Making Approach: Studying Ethnicity in Immigrant Societies. Sociological Theory, 27(3), 244–270.

Morsi’s Defense Wanted to Learn Sign Language

In another terrific article by Peter Hessler (March 10, 2014), a journalist covering the ongoing revolution in Egypt, he remarks that Mohammed Morsi’s defense wanted to learn sign language to communicate with their client through the soundproof cages in which they are kept in the courtroom.

“At the next hearing, another defense lawyer stood up and requested that the trial be delayed until his legal team and its clients were able to learn sign language, so they could communicate. (The judge rolled his eyes–request denied.)”

The Task of the Interpreter and Walter Benjamin

I have always had a nagging feeling that interpreting is one of the most important human activities. Interpreting is valuable not only for the participants immediately involved, but its also a fascinating demonstration of the human capacity to do things with language.

Language is interesting because virtually no part of our human existence can be fully understood or thoroughly appreciated without language. Indeed, over the past 100 years philosophers as different (and in some ways as similar) as Bertrand Russell and Martin Heidegger have spent the better part of their professional lives trying to explain just how language structures the experience of being human. Central to these thinkers – and the many who followed them – was the notion that humans have a unique and extremely flexible capacity to assign meaning to the objects and experiences we encounter in the world. Our individual and collective role in assigning, negotiating, and contesting meaning in the world can be summed up in one word: interpretation.

Loosening the Boundaries of History

Therefore it is likely no accident that interpreting – and sign language interpreting in particular – became a profession in the 20th Century. We tend to focus on the historical events that define our profession (the Ball State meeting in 1964, let’s say) or the individuals who invested their labor into moving us forward (Lou Fant comes to mind). It’s clear why. Their stories are our stories handed down through mentorship or gleaned from the pages of textbooks or from the VHS cassettes we used in my interpreting program.

However, I’d would like to make a very simple suggestion: that we zoom out from our individual profession – if just briefly – to put ourselves and our collective history into a larger context. My is strategic. I am suggesting that we widen the scope of our own history, and in so doing recognize (and advocate for) the larger significance of interpreting in society. My imperfect example is to take a look at an essay written in 1923 by Walter Benjamin.

Walter Benjamin was a German literary critic, philosopher, and translator whose life of influence and tragedy is too dense to tell here. What is important for us is that in 1923, Benjamin wrote an introduction to his translation of a collection of works by the French poet, Charles Baudelaire. The introductory essay was called The Task of the Translator, and in it Benjamin lays out his approach to the nature of translation and some of its main challenges. One caveat: it’s true that the pragmatic considerations of translators appear very different from what we think of as interpreters. But a closer look at Benjamin’s text reveals language issues that transcend practical differences.

Walter Benjamin’s The Task of the Translator

I would like to focus on two main examples that I find especially relevant in Benjamin’s essay.

On the Limits of Fidelity

“…no translation would be possible if in its ultimate essence it strove for likeness to the original.” – Benjamin

The fundamental principle of translation and interpretation is the notion of fidelity. But Benjamin suggests – and working interpreters know – that strict formal fidelity is part of the problem, not part of the solution. We’ve all seen this, haven’t we? Those moments when we interpret something with undue literalness. We say things like, “that was too English” or “you’re talking in ASL” to indicate this simple concept. Awkward literalness isn’t a result of simply choosing the wrong variable in an otherwise balanced equation, like systematically replacing the red blocks in a Lego house with otherwise identical green blocks. There is something about interpreting which escapes formal calculation. And yet when we see amazing interpreters at work, we feel that “click” that something has come together in an entirely original yet accurate way. We recognize that provisionally – in the moment, in the set of circumstances at the time – a great interpretation performs the function it was intended to have. What Benjamin argues clearly (and more elaborately in his essay) is that fidelity, strictly speaking, is not always the best way to evaluate the success of a translation or an interpretation. This may seem obvious to us now. But remember: he was writing over 40 years before RID was came into existence, and still long before any systematic work had been done in interpreting theory.

On the Impossibility of a Final Interpretation

“…all translation is only a somewhat provisional way of coming to terms with the foreignness of languages.” – Benjamin

Even the best interpretations are always partial. In the everyday life of interpreters, there is a common (but under-analyzed) practice of commenting on the ways that we would have interpreted something that another interpreter signed or voiced. Yet have we fully appreciated the fact that this common practice is only possible because interpretations are indeed always partial, always “provisional”? Indeed, we always could have signed or voiced something different, and yet there is no need to imply that the first interpretation was inadequate. There are always openings for other interpretations which add something unique or relevant. This is not simply the result of peer violence, where interpreters belittle one another’s work (although it is sad when it stoops to that level). Instead, this is an indication that interpreting is our slippery attempt to make sense of the linguistic and social situations that we find ourselves in. A word of caution: this does not mean that all interpretations are equally valid. Benjamin is very clear that “bad translations” (his words) exist and perhaps dominate the world of translations. But it does suggest that even our best work will need to be refined over time, and that no interpretation can claim a superior finality.

Relevance Today

The conclusion I draw from this difficult essay is rather simple. Benjamin remains a significant literary and theoretical figure today – probably more so than when he was alive. There is great value for us in realizing the affinities between our work as interpreters and aspects of Benjamin’s work 100 years ago. Not only do we open up new opportunities for us to think about our own work, we can also open up dialogue with other fields of study. I recognize that this may not be attractive to all interpreters, nor does it make us better skilled or better paid interpreters overnight. But for some of us who are trying to meet new educational requirements for certification or trying to expand our professional knowledge base, this might provide new and useful opportunities.

I believe Benjamin’s essay is relevant today because it shows that the history of our profession is not simply our history. Rather, we exist today in part because of a number of social, political, and – yes – philosophical conditions the 20th century. What is at stake in interpreting is not only the important role of language mediation between the often-marginalized sign language community and the non-signing majority. Interpreting is intimately connected to the most profound and fundamental shifts in economic organization and philosophical thought in the past 100 years. With this recognition in mind, we may be able to argue forcefully that while our numbers may be small, we are nonetheless significant and deserve more than passing attention. It is to the benefit of society at large – not only to working interpreters – to recognize our important place in history.

*This is an incomplete short piece I started writing over a year ago and never quite finished. I present it here so I can just move on.

Why ASL Matters

The intellectual history of ASL and Deaf studies is a fascinating one. It has yet to be written. But if I get to tell that story, here’s how part of that story will go.

Interpreters and hearing scholars, often working alongside Deaf collaborators, recognized that “Deaf gesturing” was much more than gesturing: it was an actual language. To legitimize calling it language, these scholars drew heavily upon the structural linguistics of their day to show that ASL could be studied and described as any other language, albeit without a written form. While Deaf advocates have always existed, this linguistic research drew upon the anthropological idea of culture to reinforce their claims that ASL belonged to a social minority and could be studied alongside a study of the everyday life of the Deaf community. A powerful idea was born, which, alongside the commodification of interpreting services and social service in general, created a relatively coherent and internally consistent argument about Deaf difference, oppression, and justice.

There was just one problem: much of this literature, for very good reasons, uncritically assumed the ideas of majority academic research and popular thought at the time. Until today, these ideas have been relatively unchanged. (I would argue that the early articles in Sign Language Studies are an un-mined source of new ideas for us today.) Much like geography departments today, interpreting programs and Deaf studies programs are under constant pressure to justify their existence. They must answer the question: why does ASL matter? Why do we need to know anything about the Deaf community? The usual response about Deaf people being an oppressed minority is true, but insufficient. I think Giorgio Agamben provides a very thoughtful way forward. This thought came to mind as I was reading selections from his book Potentialities (1999).

In his essay The Idea of Language, Agamben describes language as revelation like this:

“…the content of revelation is not a truth that can be expressed in the form of linguistic propositions about a being (even about a supreme being) but is, instead, a truth that concerns language itself, the very fact that language (and therefore knowledge) exists. … humans see the world through language but do not see language.” (40)

And in a later essay On Gesture, he describes

“If speech is originary gesture, then what is at issue in gesture is not so much a prelinguistic content as, so to speak, the other side of language, the muteness inherent in humankind’s very capacity for language, it’s speechless dwelling in language. … gesture is always the gesture of being at a loss in language…” (78)

These two quotes matter for the following reasons.

First, they show that despite many years of recognition, visual languages still haven’t made a strong impact in precisely the most important philosophical circles that they should. You can see that Agamben’s notion of human language is still very oral/aural.

Second, don’t be too harsh on Agamben, because within these short excerpts you can already see that there is great potential here to extend these arguments to ASL. In fact, I think we can start to see why visual languages have been resisted for so long. It’s not just longstanding prejudice against the body and against sign languages. It’s also about the historic understanding of being as the one who responds to the event of spoken language, even when one can’t decipher language. Philosophers have always been fascinated by sign language communities — if only marginally — because they represent the limits of linguistic communities.

ASL matters because it is the point where gesture, which is typically the loss of language, becomes language itself. We should not try too hard to equate visual languages with spoken language, but to demonstrate how they push philosophy beyond its ontological limits.

Deaf Community as Imagined Community?

Imagined Communities

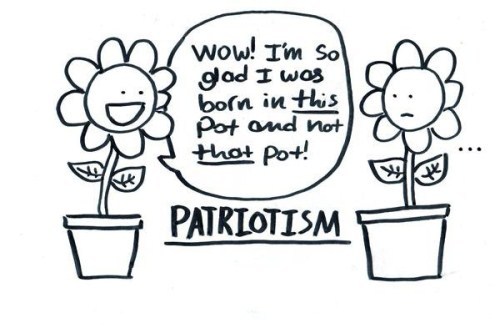

Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities should be required reading at all interpreter training programs. (I just added it to the Interpreter’s Library.) The thesis is quite simple. The idea that you and I belong to a community called a “nation” is an enormous stretch of reason, given that we can’t possibly be in daily relationship with the other people in this “national community”. Yet, this is precisely the ideology of nationalism, which seeks to collectively represents people on the “inside” against people on the “outside”. Anderson never says that imagined communities aren’t real simply because they are imagined. On the contrary, imagined communities have even more power because they are imagined. If this seems trivial, take a quick glance at the news coming out of Crimea this morning.

Politics of Language

Language is central to Anderson’s argument. The bulk of Imagined Communities is about how nationalism took off and where nationalism got its start (spoiler alert: its not just about Europe). One of the major players here is language, because language became such an important element of nationalism. Even in the U.S., where the dominant language of English is hardly owned by U.S. citizens, English-only policies have been regularly introduced for well over a century to distinguish so-called “assimilated” immigrants and foreigners from “native” residents. Yet, Anderson reminds us that what is truly at stake in the politics of language is its ability to create a strategic boundary around a political community.

“It is always a mistake to treat languages in the way that certain nationalist ideologues treat them — as emblems of nation-ness, like flags, costumes, folk-dances, and the rest. Much The most important thing about language is its capacity for generating imagined communities, building effective particular solidarities.“ (133)

Why should interpreters care?

Here’s why I think this is important for interpreters to think about.

First, we know that Deaf communities have always experienced social oppression in various forms. What hasn’t been sufficiently explored is why much of this has taken place within the field of language. In my view, the literature in Deaf studies and interpreting studies has over-emphasized the direct anti-Deaf discourse by people like A.G. Bell, but hasn’t sufficiently challenged the nationalist ideas that makes language discrimination possible in the first place. When the English language is used as a “national bond” for U.S. citizens, it justifies the exclusion of non-English speakers (Deaf individuals included). In other words, the U.S. as a “nation” is an imagined community – it is not simply “real” in any everyday empirical sense. (As a side note, it is fascinating to me how many Deaf and hearing ASL users have made anti-immigrant comments to me, always failing to recognize that every argument against immigrants in the U.S. – true or not – has been used to discriminate against Deaf people, too.)

Second, the politics of language isn’t just about hearing English-speakers. As I said in my previous post, Deaf consciousness in the U.S. emerged alongside ideas of culture and nationalism in the 1880s. Sign language in the U.S. (even before it became “ASL”) became a signature feature of the U.S. Deaf community, and for very good reasons which my readers probably do not need explained to them. But the story isn’t quite as clear-cut as it seems. If we want to take Anderson seriously, we should recognize that language identity is always a political strategy, not just an empirical reality. And like all strategies, it includes some things and excludes others. ASL research — again, for very good reason — has tended towards ASL purism in the confines of a media room with Deaf-of-Deaf participants. No significant research exists on the everyday diversity of language use in mixed Deaf-hearing workspaces, for instance. So I wonder how this imagined community that Anderson talks about also applies (as he says it does) to minority social groups like the Deaf community. It’s not just about dominant groups; it’s about the conditions of political recognition for minority groups, too.

Third, this starts to provide a more interesting context for understanding Deaf advocacy. The value of the strategy of rigid Deaf cultural distinction (see Mindess 1999) and ASL purism is that makes it possible to advocate for recognition of ASL as a real language at a time when many people are still ignorantly skeptical that ASL should count. ASL has justifiably been seen as probably the marker of the Deaf community, or as Anderson says, an “effective particular solidarity”. But in doing so, we should always be cautious about believing in the idea of linguistic or cultural purism itself, an idea that is tied to the conditions of Deaf oppression in the first place.

Deaf Community as Imagined Community?

Calling the Deaf community an “imagined community” sounds risky. Many people have lobbed misplaced and ignorant criticisms at the Deaf community for not being a “real” culture, a “real” social group, not using a “real” language. The reaction has been to dig our heels in to the slippery soil of the “real”. And we respond. Yes, Deaf people are a “real” culture. Yes, Deaf people use a “real” language. Yes, Deaf people are a “real” oppressed social group. Indeed, much of the research on ASL, interpreting, and the Deaf experience has defended this position. This is somewhat unfortunate, in my opinion, but entirely understandable. But the side effect is that we are less and less capable of challenging oppression on its own conceptual grounds. We end up playing a game in which the rules are already set against us. Suggesting that we understand the Deaf community as an imagined community (per Anderson) doesn’t compromise the credibility of Deaf advocacy. Instead, it advances advocacy a step further by suggesting that not only do Deaf individuals not need to justify themselves to hearing individuals, hearing critics themselves don’t have a foundation for judging what a “real” language, culture or social group is in the first place. But it may also mean that as interpreters, we need to let go of simplistic divisions between what we think of as “Deaf” and “hearing”, what we view as “pure” ASL, and to challenge the ideas (such as some versions of nationalism) that make Deaf oppression possible.

Why is ASL so important to Deaf culture?

Introduction

This post cannot answer the title question thoroughly. Nor is this a “study” of Deaf individuals’ narrative frameworks for understanding ASL and culture. (Interestingly, no such research exists.) Rather, this is an attempt to understand how ASL and Deaf culture have been conceptually linked, and how this particular link between language and culture is a double-edged sword.

In his 2005 article on “Ethnicity, Ethics, and the Deaf-World”, Harlan Lane provides a well-argued critique of applying the term disability to Deaf individuals. Lane suggests that hearing people should view the Deaf community as an ethnicity, and he provides long list of properties which are intended to demonstrate that Deaf people are an “ethnicity”: language, kinship, “the arts”, social structure, values, knowledge, customs, etc. In the short paragraph describing language, Lane quotes well-known linguist, Joshua Fishman, in defense of language as a primary ethnic marker. I’ll quote the entire paragraph:

“‘The mother tongue is an aspect of the soul of a people. It is their achievement par excellence. Language is the surest way for individuals to safeguard or recover the authenticity they inherited from their ancestors as well as to hand it on to generations yet unborn’ (Fishman, 1989, p. 276). Competence in ASL is a hallmark of Deaf ethnicity in the United States and some other parts of North America. A language not based on sound is the primary element that sharply demarcates the Deaf-World from the engulfing hearing society.” (Lane 2005)

Anyone with a week of experience in the Deaf community will grasp the common sense of this statement. As Mindess quotes in an epigraph on page 110 (a quote from Schein 1989) of Reading Between the Signs, “For many members of the Deaf community, they and ASL are indistinguishable. Their self-concept is based on being Deaf and being Deaf to them means using ASL.” Interpreting students learn this simple fact from Stewart, Schein, and Cartwright (1998), too: “ASL is the language of the Deaf community.” (134) Minor quibbles aside, these are rather incontestable observations as far as I can tell. And they are – or should be – foundational knowledge of sign language interpreters.

But there is something missing for me.

Something is Missing

What’s missing for me is a history of the ideas that make the Deaf community a community – or ethnicity, or culture, or linguistic minority – and which therefore make interpreting a profession in the first place. I hope the following illustration explains what I think is missing from our current literature and creates an opening for further discussion within interpreting in the future. (See post What Do Interpreters Need to Accomplish?)

If we could summarize the above quotes in a brief assertion that sounds like anthropology 101, it would go something like this: “Language is one of the primary markers of distinct social groups.” This has been true for as far back as the historical record shows. But there’s a twist. It wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries that language took on a particularly powerful role in defining social groups in the sense that we think of it today.

What is language and culture?

The main figure in this evolution is Johann Gottfried von Herder (according to Peter Watson in The German Genius). Locke claimed that language was a natural phenomenon, not a divine gift – a transformation in thought that interpreters should certainly revisit. But it was Herder who gave language a new power it didn’t have before. It’s worth quoting from Watson’s book at length:

“Language identifies a Volk or nationality, and this, the historico-psychological entity of the common language, is for him ‘the most natural and organic basis for political organisation… Without its own language a Volk is an absurdity (Unding). … A Volk, on this theory, is the natural division of the human race, endowed with its own language, which it must preserve as its most distinctive and sacred possession.”

Herder should also be known for his advocacy a rather new idea at the time: culture. For Herder, “whatever the ‘collective consciousness’ of a Volk was at any particular time, was its culture.” (The term Zeitgeist – the spirit of the times – was Herder’s neologism.) For Herder, these concepts of Volk, language, culture, and nation are all intertwined. Ultimately, all of these features reach their height in the establishment of a nation-state, a political organization which has the authority to represent the political will of the people – in fact, the state itself is the political will of the people.

Why does this matter?

First, I think Herder’s original writings are more philosophically robust than most of what we find in interpreting literature today. This is not a criticism of books about interpreting, but it suggests that there is much to be gained from reading the original texts of thinkers who we often think of as old and irrelevant. This may not interest most working interpreters. But working interpreters deserve to know that it hasn’t interested scholars in Deaf studies and interpreting either. In other words, despite about 50 years of scholarship in our field, we still don’t know where our ideas came from. This is no small matter. And it would be a great topic for a MA thesis is anyone out there is thinking of going back to school. (See post All Interpreters are Philosophers.)

Second, I think we can detect in these excerpts the double-edged sword that is about to fall on Western civilization. This is a bit more complex, but it is very important. When Herder argues that language is the most natural, authentic characteristic of social groups, he is lending support to the idea that “natural divisions of the human race” exist, and therefore can’t be challenged. This is known today as essentialism. And he is lending support for the newly-formed nation-states of Europe. By 1945, these European states and their many counterparts in the Third World will have experienced a century of nearly unending conflict and war precisely on the basis of these “natural” human divisions. Horkheimer and Adorno will later call this the “triumphant calamity” of the enlightenment. (See The Culture Bargain post.)

Third, this is the time (late 1700s, early 1800s) that what we now call the Deaf community was beginning to take its modern form in Europe and the U.S. Notably, early texts written by Deaf individuals refer to themselves as a “nation”, not as a culture. Culture didn’t take on its modern meaning in English until the 1860s, and didn’t fall into common use until the 20th century. Interestingly, when it did enter English in the 1860s, it was introduced by German-trained anthropologists who were trying to identify and categorize Herder’s “natural divisions of the human race”. In other words, the term culture has a particularly colonial ring to it. Culture, like Herder’s theory of language, is going to but both ways against the emerging Deaf community. The Deaf community will see itself as a “nation” during the 1800s, and by the late 1960s, see itself as a “culture” (with the aid of hearing academics, no small matter, indeed). But culture and language are also going to be the tools of oppression. Deaf people do not have Herder’s nation-state to back them up. Quite the contrary, it will be the ASL users themselves who will later be seen as deviating from the national cultural model. (See Anthropology’s Culture Problem post.)

Our ideas using us more than we are using our ideas

Lane was right: ASL matters to Deaf culture. But when we claim, as we often do, that language and culture are inseparable, it can make it seem as if this is how it has always been since the beginning of time. Or it seems that this way of thinking is “natural”. In fact, this idea is relatively recent. And this idea has cut both ways, sometimes hurting the Deaf community, sometimes empowering the Deaf community. Without attention to where these ideas came from, I can’t help but think that we are captive to these ideas. When we are captive to our ideas, it becomes hard to imagine a different world and our options for advocacy are stunted, hampered, restricted. Our ideas using us more than we are using our ideas. It is worth our time to excavate these ideas and enrich our ability to be excellent interpreters and strong advocates.

This is not a definitive answer to the question, “Why Does ASL Matter to the Deaf community?”. But it is an often-overlooked part of a larger answer.

List of references:

- Lane, H. L. (2005). Ethnicity, Ethics, and the Deaf-World. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 10(3), 291–310. doi:10.1093/deafed/eni030

- Mindess, A. (1999). Reading Between the Signs: Intercultural Communication for Sign Language Interpreters. Intercultural Press.

- Stewart, D. A., Schein, J. D., & Cartwright, B. E. (1998). Sign language interpreting: Exploring its art and science.

- Watson, P. (2011). The German Genius: Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century. HarperCollins.

Sorenson Files for Bankruptcy

Thanks to Street Leverage, I just found out that Sorenson has filed for bankruptcy (Reuters). On this blog, I have tried to emphasize the need for interpreters to think beyond the everyday. We need to understand interpreting within a broader philosophical landscape. And we need to recognize the structural – economic, political, legislative – conditions that make interpreting possible and drive the profession. (No, the Deaf community doesn’t drive the profession – we don’t have to like it, but we should recognize it if we want to change it.)

Sorenson’s bankruptcy is no small matter. They have been a huge funder for Gallaudet and for interpreting workshops (our field’s main way for advancing knowledge). While the press release claims that employees won’t be affected, I find that hard to believe. So I guess we’ll just have to see. There’s so much room for a good economic and political analysis of these circumstances. Unfortunately, we will probably have to settle for polemics.